BOULDER

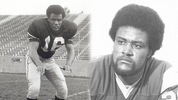

BOULDER - Cullen Bryant's toughness was legendary, but legends require time to form. And in those formative stages, they are not above being questioned.

As a football player at Mitchell High School in Colorado Springs, Bryant was a must-see prospect for college recruiters, one of whom was then-Colorado assistant Don James - a member of the late Eddie Crowder's Buffaloes staff in the late 1960s.

In researching Bryant's ability, James, later a legend himself as the University of Washington's head coach, heard this from a rival high school coach in the South Central League: "He's not tough . . . he avoids contact."

Long-time Mitchell coach Jim Hartman laughs as he recounts that story: "I thought that's what good running backs do - avoid contact."

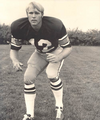

Indeed, they do, even the toughest of the tough. For anyone who played with Bryant or against him, no validation was needed. But the next spring, after he had signed with CU, Buffs coaches voted him the team's toughest player.

That reputation, complemented by his versatility, strength and work ethic, stayed with Bryant through a stellar college career and 13 years in the NFL (Los Angeles Rams, Seattle Seahawks). But it also belied a quiet and gentle off-field nature most evident to those who knew him.

Bryant, 58, died on Oct. 13 of natural causes at his home in Colorado Springs. A memorial service was held Tuesday at Trinity Baptist Church in Colorado Springs.

Bill Harris, recently retired as CU's C Club director/ assistant athletic director, said the service was attended by "a couple of hundred" people, including several former Buffs teammates and NFL players.

Bryant was eulogized, said Harris, as much for his humility as his extraordinary football skills: "If you never saw his Super Bowl ring, you never knew he had played in one (1980, a Los Angeles loss to Pittsburgh), because he wouldn't talk about it.

"He was just a big, talented and very quiet, very humble guy."

Hartman, whose backfields at Mitchell featured Bryant and Terry Miller (Oklahoma State; Buffalo/Seattle, NFL), was awed by Bryant's "great speed . . . but even better was his explosiveness. He could take two steps and was at top speed."

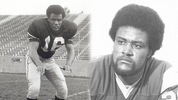

That attribute is ideal for an I-back, but CU ultimately utilized him on defense, where he tied a single-season school record with seven interceptions (43 tackles) in 1972 and was a consensus All-America selection.

In an email to CU's sports information department, former CU teammate Ken Johnson, a quarterback, called Bryant "pretty quiet, real smart, determined . . . absolutely as good as they come" and "an amazing athlete."

Not coincidentally, Bryant's toughness also registered with Johnson: "He was the one guy I actually dodged during one vs. one scrimmages."

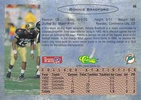

But offensive players in the NFL wouldn't be forced to account for him. After making him their second-round draft choice in 1973, the Rams made him a running back, and he played that position for them for 11 seasons and two more for the Seahawks.

Before signing with Seattle, he worked with the Rams as their assistant strength trainer, then played one more season (1987) in Los Angeles before retiring.

He finished his NFL career with 3,264 yards on 849 carries, scoring 20 touchdowns. He also accounted for 1,176 receiving yards, with three TDs.

Former Rams/Seahawks coach Chuck Knox told

The Los Angeles Times that Bryant "was an outstanding person with great character traits. When we asked him to do certain things, he'd do them; he never complained about anything.

"When he got that big body moving, it was something else . . . he had muscles on top of muscles."

Rams teammate Jack Youngblood, a linebacker, said in 1979, "When Cullen hits those holes, nobody wants to stick their nose in there. Those little 180-pound (defensive backs) just jump on his back when he runs by."

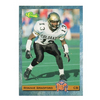

He was equally imposing on special teams. At 6-foot-1, 234 pounds, Bryant was not your run-of-the-mill return man - and special teams players of his day took notice.

"I guess some of the ends coming down on punts or kickoffs are surprised to see a guy of my size (as a returner)," he said in 1976. "They're used to tackling smaller people and might slow up or hesitate. This gives our blockers time to set up a return."

During his NFL career, Bryant returned 71 punts for 707 yards and 79 kickoffs for 1,813 yards (three TDs).

Bryant, born in Fort Sill, Okla., on May 20, 1951, took conditioning seriously, so much so that some remember him as the impetus for CU's off-season conditioning program.

Hartman, his high school coach, recalls hearing from ex-Buffs assistants that upon returning to their offices about midnight from a recruiting trip, they spied a player lifting in the weight room.

It was Bryant, who had been given a weight room key by Crowder and, like clockwork, could be counted on to work out daily during the off-season.

Said Hartman: "In a lot of respects, I think he changed the face of CU football."

Bryant also had a hand, albeit unwittingly, in bringing change to the NFL, as recounted in

The Times:

"Two years into his (NFL) career, Bryant found himself at the center of a legal case that tested the power of then-NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle to regulate free agency.

"The controversy started in 1975 when Rams owner Carroll Rosenbloom signed Ron Jessie, a former Detroit receiver whose contract with the Lions had expired. Under the 'Rozelle Rule,' the commissioner was empowered to award the Lions either draft choices or players if the teams couldn't agree on compensation.

"Rozelle ruled that Bryant must go the Lions as compensation. At the behest of Rosenbloom, Bryant headed to federal court in Los Angeles.

"At the hearing, the judge heard Bryant's legal counsel, heard the league's rebuttal and then essentially said he couldn't believe this type of servitude still existed.

"The NFL capitulated a few days later, before the judge even ruled."

Bryant, who was divorced, is survived by two adult sons, William Cullen Jr., and Brandon; a 13-year-old daughter, Brianna; and three brothers.

His sister-in-law, Wanda Bryant, said he "loved his children (and) would spend as much as he could with his daughter especially . . . he had a very close relationship with her."

In his later years, Bryant kept to himself and, unbeknownst to his family, had been under a doctor's care, according to

The Times.

Hartman said he visited with Bryant when Bryant was inducted into the Colorado Springs Sports Hall of Fame in 2000, adding his former player "spoke eloquently" at the induction.

"After that, I didn't see him for years," Hartman said. "I think the last time was in the parking lot at Home Depot. At the time, he said he had an interest in getting into coaching, but it never worked out.

"He was an immensely talented player. He was not outspoken, not a rah-rah guy . . . but sometimes those quiet guys are the toughest."

Contact: BG.Brooks@Colorado.EDU